The very first seafood product in history was a condiment manufactured more than 2,000 years ago in Greece, Rome, Phoenicia, Carthage, and later in Byzantium. It was called garum or liquamen and was as commonly used as salt at dinner tables—a remarkable accomplishment for a fermented fish sauce. This product is not made by bacterial fermentation that turns once-living matter into a rotted, stinking mess. Bacteria could not exist in the amount of salt required to make the sauce. This fermentation is called enzymic proteolysis, a process wherein the enzymes in the guts of the fish react with the salt to produce a pungent, oily brine. So more properly, it is a fish oil brine rather than a fish sauce.

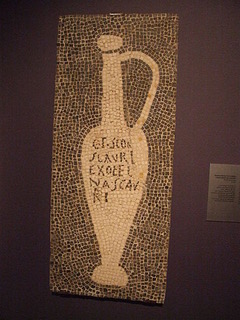

The manufacture and distribution of garum was one of the few large-scale factory industries in the ancient world and it’s packaging was as interesting and significant as the product itself. Like wine and olive oil, it was stored and transported in ceramic amphorae (amphoras) that were often used as ballast in merchant ships. Garum factories were scattered throughout the Roman empire, but mostly in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, and always near the shore or harbor. The process was so smelly that factories were often banned from urban areas. The amphoras were sealed with pine pitch to prevent leakage and the top openings were sealed with carved wooden stoppers. Interestingly, the pine pitch used with wine storage was the precursor of retsina, the resin-flavored Greek wine.

The manufacture of garum was simple and straight-forward. The innards of pelagic fishes such as anchovies, sprats, sardines, mackerel, or tuna were crushed and then large amounts of salt were added. Sometimes whole fish were used. The fermentation in hot weather took about forty-eight hours. The resulting oily brine was strained off and bottled in the amphoras. Reputedly, the brine was not as fishy-flavored as one would imagine. The residue, called alec, was dried and also was valued as a seasoning for foods and a medicine for treating burns.

There are two basic methods for making garum in the home kitchen—one requires fermentation and the other does not.

Method Number One

Take a number of small, fresh fish and place them on parchment baking paper lining metal sheet pans. Cover the fish with a thick layer of sea salt, place the trays in the sun and protect them from flies using cheesecloth as a barrier. Turn the fish twice a day for several days until the fermentation is complete. Scoop the fish into a strainer with a glass bowl beneath it. The liquid that seeps into the bowl is the garum, and it should be clear with a color ranging from light yellow to amber. If it turns opaque, throw it out. Store in glass jars in the refrigerator, where it will keep indefinitely. Use it in small amounts, like a teaspoonful, to flavor grilled or roasted meats or poultry during serving.

Method Number Two

Garum Ingredients

- 2 pounds small, whole fish such as sprats, sardines, or anchovies (can be frozen)

- 1 pound sea salt or kosher salt

- 2 ½ tablespoons dried oregano

- 1 tablespoon dried mint

- 2 ¾ pints water

Rinse the fish under running water but leave them intact and do not gut or clean them. Combine all ingredients in a large pan. Bring to a boil and boil for 15 minutes, Crush the fish with a wooden spoon and boil for 20 more minutes. WARNING: Cats love this! Use a colander or coarse strainer to remove all the larger fish pieces, then strain the remaining liquid through cheesecloth several times. The resulting clear liquid will be the unfermented garum. Use it in a similar manner as in Method Number One.