Seafood was the driving force behind the only prehistoric culture in the world that evolved without agriculture: the Calusa chiefdom in the shell middens of south Florida. They were a notch below a true civilization like the Maya, lacking two of the major elements needed for that designation: cities and a written language. That said, as Tamara Jager Stewart, writing in American Archaeology observes, “The Calusa may have been the only ancient people in North America who established a kingdom without practicing agriculture. Their sophistication and fierceness enabled them to resist Spanish domination for some 200 years.”

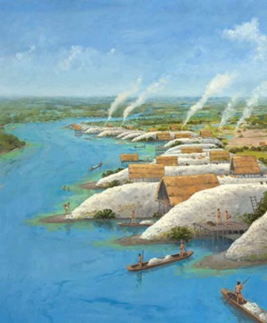

In order for a culture to grow and expand their territory, there must be an adequate supply of food. The Aztecs depended upon agriculture, especially maize, and used taxation in the form of tributes paid to the central government by the crop-growing villages in the outlying rural zones of what later was called New Spain, and later, Mexico. But lacking those crop resources, how did the Calusa become the dominant tribe in Florida, with a population of 20,000 to possibly 50,000, before the Spanish seized control of the region? Tamara Jager Stewart noted, “The Calusa developed a politically complex society with sophisticated architecture, religion, a military…long distance trade, and social ranger without being farmers.” No, they were fishers, not farmers, and they developed specialized methods of harvesting seafood. In the first place, at Mound Key. They created their own environment. “The entire island was constructed by human hands,” writes Jason Urbanus in American Archaeology, “built up with hundreds of millions of seashells, fish bones, and other materials.”

Mound Key, Florida. Illustration by Martin Pate.

Courtesy of National Park Service

And it took them a thousand years to do it, roughly from A.D. 500 to when the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s. Mound Key covers 125 acres and rises to a height of 30 feet (9.1 meters) above sea level. Its volume of seashells is about 21 million cubic feet, or about a one-quarter that of Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza. But, as University of Georgia archaeologist Victor Thompson observes, “Nobody ate the Great Pyramid of Giza before they built it. That’s exactly what you have at Mound Key. All of this is food waste. It is, in essence, a consumed landscape and then a constructed landscape.” Although Mound Key is overrun with vegetation today, 500 years ago it would have been quite dramatic. “It would have been gleaming white,” says Thompson, with geometric works in the middle of the bay. It would certainly have made a statement.”

At the highest point on Mound Key, the Calusa built an oval structure about 80 feet (24.4 meters) long and 65 feet (19.8 meters) wide, making it one of the largest Native American buildings in the Southeast. It would probably have been the domicile of the hereditary Calusa chiefs. Archaeologists estimated that this “palace” could have held around 2,000 people, roughly the entire population of Mound Key when the Spanish arrived.

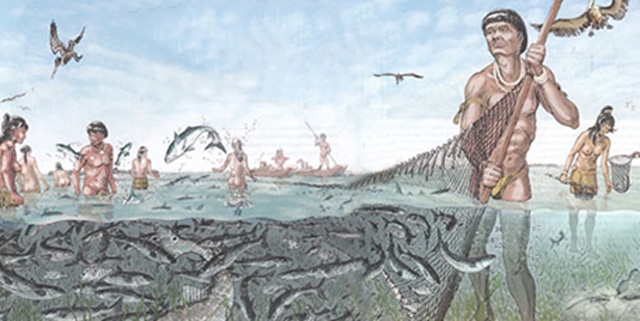

Illustration by Merald Clark, courtesy of the

Florida Museum of Natural History.

Another spectacular construction project was the digging of the great canal that bisects the island. It was nearly 2,000 feet (610 meters) long and about one hundred feet (30.5 meters) wide. At the mouth of the canal, the Calusa constructed rectangular tanks called watercourts. Archaeologists theorize that they were built to hold schools of fish diverted from the canal until they could be eaten, smoked or dried for later consumption. Scores of men and women using nets made of the fiber from cabbage palm leaves could have easily diverted the fish into openings in the berms that led to the water courts. Nets or wooden gates could have closed the openings, trapping the fish inside the watercourts.

Jason Urbanus notes, “There is evidence that wooden racks stood near the watercourts where fish could be processed, dried, and smoked… The Calusa had engineered an almost perfect system to maintain and exploit their food resources without the need for large-scale agriculture.”

But what kinds of fish were the Calusa eating? The waters surrounding them were filled with some of the most delicious fish found anywhere, including flounder, snappers, sheepshead, seatrout, and red drum (commonly called “redfish”). I’ve eaten them all and can verify their tastiness, but the Calusa were less concerned with their flavor as much as their small size, which made then easier and quicker to dry and smoke. So, they preferred what today we would call “baitfish,” namely pinfish (a type of porgy), pigfish (redmouth grunt), and hardhead catfish (similar to gafftopsail catfish). Since their only cooking utensils were clay pots and possibly wooden grates for smoking and grilling, they could not fry or bake seafood. Except in some cases, mollusks in their shells placed on coals. In my opinion smoked or dried fish are more palatable than boiled fish. They also caught, killed, and consumed mollusks, crustaceans, sea turtles, and some land animals, such as deer.

And what became of the first seafood society? For a while the Calusa were protected by the Spanish settlers of Florida, but after 1702, the English occupied St Augustine and began attacking the Spanish garrisons in Florida. They destroyed them and the missions, scattering all the Florida Indians, who were often taken as slaves or succumbed to infectious diseases brought by the Europeans. The Calusa survivors fled to Cuba, where they were assimilated and faded away as a tribe.